Making the Shift Toward Tracking Observations

I've been speaking with many secondary school teachers recently about how we might track observations and conversations in the math classroom, for the purpose of assigning a level of understanding and formally contributing to a student's overall achievement in a course.

When it comes to keeping track of marks, many teachers feel uncomfortable with evaluating what they see and hear in the classroom, much more so than evaluating what they see on paper. We feel, perhaps because observations are not as tactile as a handed-in worksheet, that an evaluation of what we see in class is more subjective, and may be called into question more than an evaluation of a product.

|

| As teachers, we are often much more comfortable using products to evaluate student understanding. |

We trust our professional judgment with products (without even questioning it) much more than with observations. But in reality, this process is not that different than when we create and evaluate paper products...

Creating & Evaluating a Product

(I'll use a quiz or a test as an example, but really this could be any paper/digital product we ask students to complete.)

When we make a quiz or a test, we very carefully choose problems that reflect the course's curriculum expectations. We use our professional judgment to decide the level of difficulty of the question, the number of questions, and the order of the questions presented to the students.

We use our professional judgment to decide which hints or formulae to provide, and how much workspace on a page to provide for each question.

In terms of evaluation, we use our professional judgment to decide what each question is worth (1 mark? 3 marks? 5 marks?) and how we will break down the marks for each question (1/3 if the bare minimum is written down, 2/3 if most of the process is there, 3/3 if the process is there and the answer is correct).

When we can, we even try the test questions in advance to anticipate what we might see on the test, as well as make sure the numbers work out, or there isn't something weird that's going to pop out of the answer.

Many of us take this process for granted - we've become "good" at designing tests, and knowing whether an answer given is worth 1, 2, or 3 marks out of three. And we feel very comfortable giving a student back a test on which they received 23.5 out of 38, and recording that mark to contribute to their overall achievement in a course.

Creating and Evaluating an "Observation"

Perhaps surprisingly, the process is exactly the same for tracking and assigning a level to what we see and hear of students in class. BUT, we have to recognize that what we typically consider to be observing (walking around the class to make sure everyone is on task, informally checking in with certain students, questioning what students are doing, answering questions when asked) requires a bit more structure for an evaluation to take place.

When we are going to be formally observing students, we as teachers have to prepare just like we would for a test. We have to ask ourselves:

- Which curriculum expectation am I assessing?

- What question(s) will I be asking the students to work on that match this expectation?

- In what order will the questions be presented?

- What hints will I provide? And when will I provide them?

- Have I tried the question(s) in advance to anticipate what I might see students try?

- How will I know the difference between students achieving at level 1, 2, 3, or 4?

From that last prompt comes a series of other questions for which, again, we take our professional judgment for granted when we are marking a test:

- What specific vocabulary/terminology/structure am I looking/listening for?

- What problem solving processes am I looking for?

- How will I know when a student has "got it?"

|

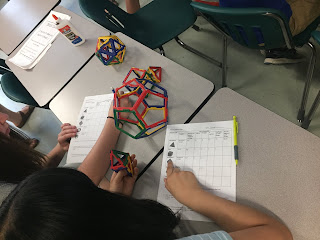

| Students are tasked with exploring platonic solids. As we observe them build their shapes, what are we looking and listening for to evaluate their understanding? |

Knowing what to look and listen for, as it ties in with a specific curriculum expectation, will make it that much easier to evaluate the level of a student's understanding.

Making the Shift

Perhaps the biggest shift is in how you will track what you see as you observe, so that what you see can contribute to a student's overall mark. Paper checklist? Google Form? Photos and videos? It truly is a personal preference - there are lots of suggestions here, and I hope to add more soon.

This may feel like a lot of work, however keep in mind that not only does this process get easier over time (remember how much longer it took you to set a test when you first started teaching?), but the point of assessing observations is that it can replace a product-based assessment, on the road to triangulating sources of evidence. This is not meant to be done in addition to your current stack of marking.

Perhaps that becomes the first observation you track - observing an activity that will replace a worksheet or other product. I would love to see/hear what you try!

Love this! I think this looks a lot like what happens in a Primary classroom, and I'm excited to see it in a secondary context. I often think that the main thing holding me back from taking an Intermediate position is that I don't now how I would turn all of my observations into a percentage come report card time.

ReplyDeleteA few years ago I started putting my exact learning goals for unit at the top of my anecdotal record sheets. It really helps me to stay focused on what I want to notice when I am conferring and observing.

Hi Lisa! I think as long as your observations are aligned with curriculum expectations (as it sounds like they are, with your learning goal prompts on your record sheets), you can absolutely evaluate what you see. It might help to include qualifiers (what indicates a level 1 understanding? Level 3?) right on your page, too? Something like a single-point rubric might also be useful too :)

Delete